The Chuck Lowe Experience

George L. Bradley

Really, what is life without snakes?

--- pers comm. C. H. Lowe near Alamos, Sonora, June, 1987---

George Bradley, age ca 14 with Large Crotalus scutulatus. Prescott, AZ. Photo by Diane Bradley.

After a long and crisis-ridden drive north from Tucson, we take the 219 exit off I-40 east of Flagstaff. Here, we are hoping to grab a long overdue meal before setting out on the night’s snake hunting activities. As we enter the Twin Arrows Trading Post, I notice a woman behind the counter and a row of tables along the side of the room. At the far end, two local men sat unobtrusively listening to a small transistor-type radio on the table between them. My companion taps my shoulder, points directly at them and says, “Navajos – strangers in their own fucking land!” And yes, he says this loud enough so that everyone in the place could plainly hear him.

As we approach the counter, I can see that my companion, now in full blood-sugar deprived mode, is obviously agitated. This is not good! As we order our fast-food-microwaved-sandwich-like fare, I can see that my compadre is getting increasingly tense. As he stares at the floor and roughly rubs his balding and sun-reddened head with both hands, I brace myself.

Suddenly, his face now as red as the top of his head, he spins around and yells, “Son of a bitch,” then walks briskly to the back of the building where the two men are sitting and demands their radio. Yes, he demands their radio! Though clearly horrified by this six foot four bearded madman, one of them weakly utters “no” under his breath, and puts his hand over the small device. Now crimson with rage, my companion grabs the small radio and pries it from the man’s surprised fingers. Trying not to piss my pants, I quietly ask him, “What the hell do you think you are doing?” He ignores me. The two men, now too stunned to react, sit there in shocked open-mouthed disbelief. About this time, I begin planning my hasty exit from the building. He fumbles with the radio for a moment then finds the power switch and turns it off.

For a few very long moments total silence hangs in the air like a cabbage fart in a crowded church. Staring at the two men, he grumbles, “You were disturbing everyone in this establishment with this noise.” Again, I glance over my shoulder making sure that my exit from the building is unblocked and I have my set of car keys in hand. My companion, at this point, has clearly lost his mind and is totally on his own.

Brad Daniels, George Bradley, and Jim Higgs Turning trash at old Hillside Dump., ca April, 1974. Photo by Chris Baptista.

Then, with a voice he could have patented for effect, he roars without an increase in volume, “If I give this damned thing back to you, do not turn it on again until no one else is here to bother.” By this point, I have backed up ten paces toward the door and have half turned ready to bolt.

Through trembling voices, they both mutter “okay.” He then opens the back of the radio, pulls out both small batteries, throws them onto the seat of the booth next to them, and places the radio back on the table. I follow him back to a table near the door where our sandwiches are nervously handed to us. In a silence too loud to describe, we eat our soggy food as I ponder what is going through those poor fellow’s minds. Embarrassed, I hide my gaze from theirs as I can’t help from putting put myself in their shoes. Halfway through our meal, they both get up, carrying their radio with them, and walk up to the girl behind the counter. They whisper something to her before they leave and she shakes her head in the affirmative. I begin thinking -- ambush! They are going to jump us as we leave the building.

I made my food last as long as possible, but such foodstuff can only be savored so long and is best swallowed without extensive exposure to the tongue and taste buds. Thus, all too swiftly, we were ready to leave. As we exit the trading post, I let my companion lead the way and hang back until he reaches our car and opens the door. Standing in the building doorway, I intensely scan the parking area for anything unusual. I am hoping that our two friends are gone, and they seem to be. Relief is a mild word for my feelings.

My companion this night -- Doctor Charles Herbert Lowe, Junior, -- a.k.a. Chuck, Bajo, Chief, Desert Rat, Mr. Sahuaro, Charlie, Chuck Lowe and his All Girl Lizard Show, Mr. Desert, Chuckles, Uncle Chuckles, Boss, Bossman, Packrat, or Lowenbrau. If there were ever anyone whose personality could overshadow the oddities and eccentricities of my own behavior, and by comparison make me feel and seem normal -- it was Lowe.

Chris Baptista and George George Bradley with boa. Prescott, AZ, ca 1974. Photo by Elizabeth Baptista.

Chuck was a character of extremes, and the story above illustrates but one of those extremes. The terms larger than life and force of nature both apply to this man as if they had been coined on his behalf. He was, I believe, the only person of real genius I’ve ever met, but was as often as not forced to use this intellect in concert with his powerful form to quell those battles brought on via his idiosyncratic and sometimes less than diplomatic personality. His normal speaking voice had an almost calming effect belying both his physical size at six feet four inches and the booming volume for which he could amplify said voice at the drop of a hat. His super-charged demonstrations of paranoia, selflessness, selfishness, compassion, vindictiveness, charity, or anger are legendary.

Of this list of personality traits, paranoia stands out like a gout-inflamed toe. He was constantly worried about and convinced people were stealing from him, whether it be material items or his ideas. This often got the better of him and fed on itself. He would often hide things he thought to be valuable. Unfortunately, he would soon forget he had hidden them, and when not found in their normal place, were assumed stolen. I knew I was a suspect in these crimes of his imagination, but felt in good company, as everyone else around him labored under the same curtain of suspicion.

The man could treat you like a criminal one moment, then give you that last money he had the next. Just about everyone who knew this man had a collection of, what are now known far and wide as Lowe Stories. This many-sided individual touched those around him in varied ways. There were those who loved him, those who hated him, and there were those, who, like myself, both loved and hated the man (sometimes simultaneously). A whole host of people have threatened to chronicle the complexities, absurdities, and wonders of his life in book form, and I hope these works will appear. In the next few pages I will touch on a few of my own experiences with this remarkable character.

George Bradley collecting Prosopis specimens from Near Hillside, Yavapai Co. Photo by Karen Schuster.

My first contact with Lowe came in the summer of 1980 with a late night phone call. At the time, my wife, my new baby daughter, and I were living in a trailer park on the outskirts of Prescott, Arizona. As I answered the phone that night, I could never have guessed the ramifications it would have on the lives of myself and indeed, my new family. I actually thought someone was pulling my leg when he introduced himself and I heard little of what he said in the beginning as I tried sorting out who might be playing a trick on me. Soon, however, I realized that the unique voice on the other end of the line was indeed Lowe himself. He had heard through the herpetological grape vine (yes, this exists) that I had several specimens of Rosy Boa from near Bagdad, Arizona. He was writing a revision of that species and wanted to borrow those specimens for some measurements and scale counts.

I must confess, his book The Vertebrates of Arizona was one of my bibles at the time and I was a bit awe-struck that he would be calling me. This book, with its wonderful sections on the natural vegetation of the state changed the way I looked at the deserts, forests, woodlands, and grasslands in my world. He asked me about my plans for college and wanted to know if I might be interested in someday working under him at his lab at the University of Arizona. After chatting for a bit, he invited me to visit his lab. Of course I sent him the specimens right away.

In 1983, I moved to Tucson with my family in order to attend the University of Arizona, and chose this school almost entirely because I wanted to work under Lowe. Being work-study eligible, I knocked on his door day and night in an attempt to get a job, any job in his lab. Occasionally a graduate student or Cecil Schwalbe, the Collections Manager would answer only to tell me that Lowe was out of the office, out of town, in Mexico, or otherwise unavailable. Finally, I strolled into the Departmental office and explained my situation. E. Lendell Cockrum, the mammalogist and long-time Department Head, listened to my story for a few minutes then broke in with, “You don’t want to work for Chuck anyway, he’s not good to work for.” Reeling, I said “I’m a herpetologist, that’s why I’m here.” “No” he said, “I’ll find you a job somewhere else.” Thus, from 1983 to 1985 I worked at the University of Arizona Herbarium.

In the spring of 1984, I took Lowe’s herpetology class. Here, finally, surrounded by trays of preserved specimens, identification keys, and technical discussions he could see that I was in my element. He could also see that the other students would gather around my table to ask questions. At the end of the course, he made sure he had my phone number and address. I thought this to be a good sign. It was.

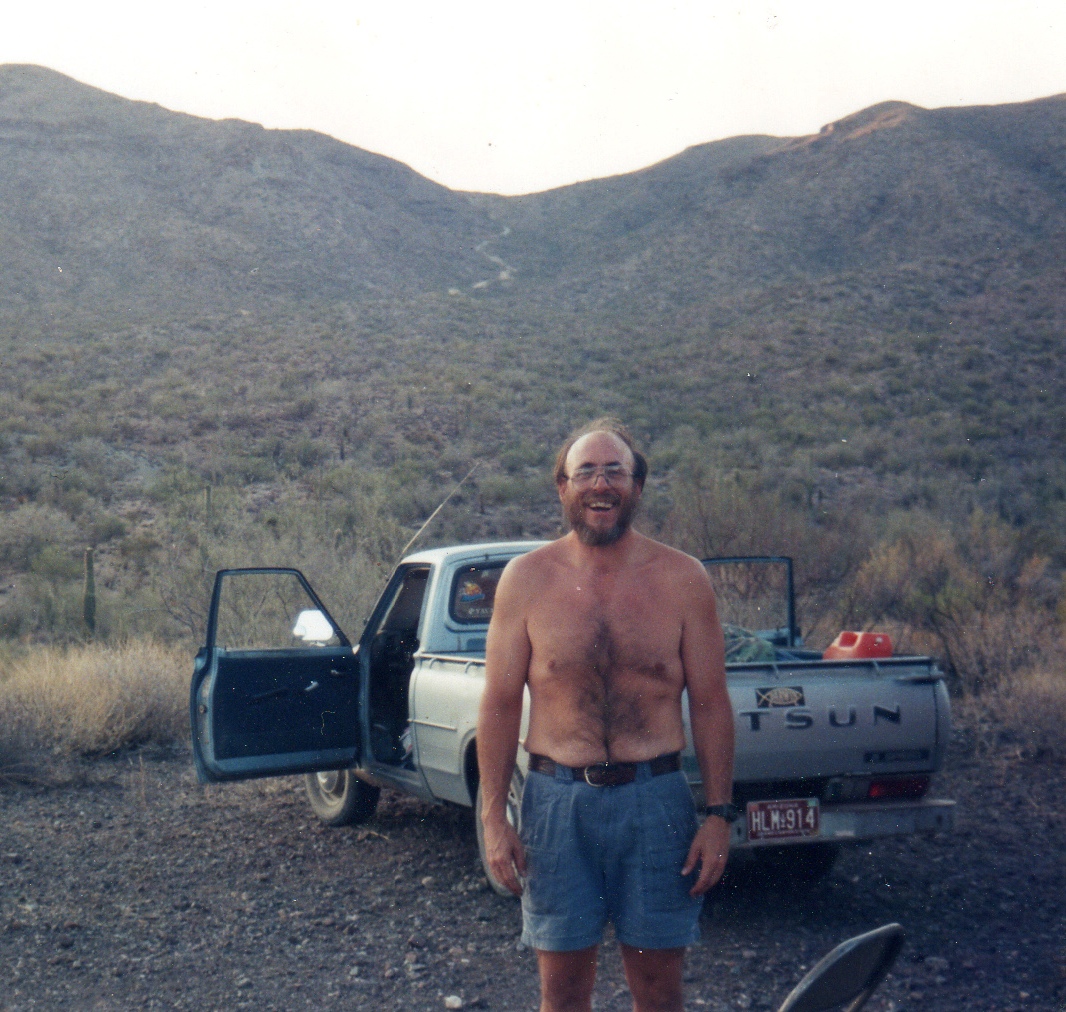

George Bradley at camp. Bullard Peak, Harcuvar Mts., AZ., 7 June 1996. Photo by Chris Baptista.

That summer, and in 1985 he paid me to conduct some field work for him and he seemed very pleased with the results. Still, it was with some surprise that I received a call from him in the early fall of that year. He wanted to interview me for a job in the lab, actually not just any job – THE JOB – Collections Manager of the amphibian and reptile collection. I was stunned! Although still in school, I could not pass up this opportunity. I said, yelled, screamed YES!

My interview for the job was pure and classic Lowe. Very late one night the phone woke me from a sound sleep. It was Lowe. He said, “It is university policy that I interview you as part of the hiring process, and I need to ask you some questions to better ascertain your abilities to fulfill this position. Are you ready?” Now a bit nervous, but still partially asleep, I said “fine go ahead.” After a moment’s pause, he asked, “Do you know anything about amphibians and reptiles?” On a lark, I replied, “They’re found under rocks aren’t they?” “Yes, they often are,” he said – “you’re hired I’ll see you Monday morning.“

Although working for him in the collection and laboratory had its own unique set of advantages and difficulties, being in the field with this man was exhilarating, exhausting, frightening, maddening, impossible, and wonderful. My first real in-the-field experience with Lowe was on a trip into southern Sonora to collect specimens and help one of his graduate students with her project. This is where I became abundantly aware of Lowe’s eating problems. Eating problems? For one thing, he forgot to eat. Then, when he did remember to eat, it was very likely a piece of chocolate cake or a Snickers candy bar. This might not have been such a problem if not for the too-oft accompanying blood sugar induced craziness exemplified above. This, combined with Lowe’s over-the-top personality and powerful ego, often lead to trouble, and Mexico is one place where a little trouble can grow big in a hurry.

The trip started out great! I was given free rein to wander about taking notes on the birds and herps of the thorn forest. I even collected some plants. I was in nature-geek heaven, surrounded by Elegant Quail, Vine Snakes, Magpie Jays, West Mexican Whiptail Lizards, Trogons, Yellow Grosbeaks, Indigo Snakes, Streak-backed Orioles, and Spiny-tailed Iguanas. As afternoon turned to evening and we hit the road, I was treated to Mexican West Coast Rattlesnakes, Mexican Short-tailed Snakes, Black Banded Geckos, Mazatlan Toads, Tropical Lyre Snakes, Blunt-headed Tree Snakes, and Cat-eyed Snakes. Yeah, I was feelin’ it!

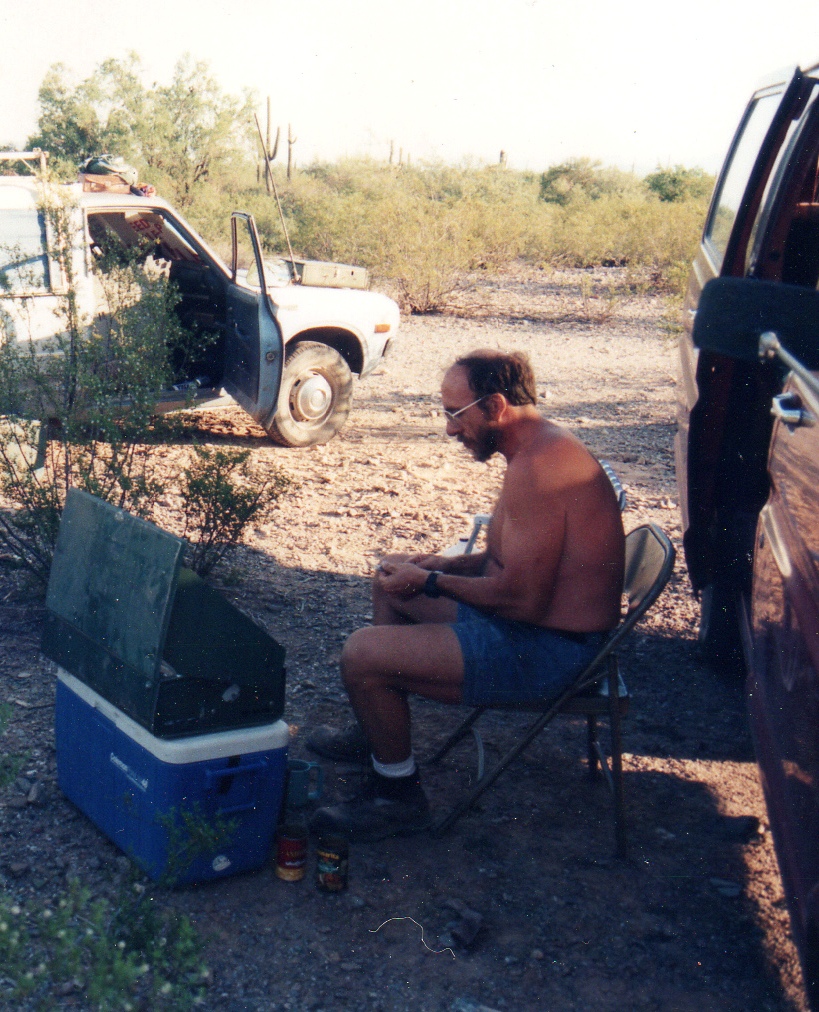

George Bradley at camp early AM, 10 Aug 1996, Vekol Valley, Arizona.

The next morning we drove out on a bumpy dirt road into the thornforest. As we made our way through a small Indian village, Chuck suddenly braked hard and we came to a skidding and dusty stop. I yelled, “What! Did you see something?” Without a word, Lowe frantically searched for something in his left hip pocket and I looked around to see that everyone in the village was staring right at us. I glanced back at Lowe just in time to see him point a pistol out of his window and fire off three incredibly loud shots at a nearby fence line. Damn! With the shots ringing and echoing in my ears, I could see kids running in terror for their parents and families crowding into their huts. I screamed, “What the hell! Where did you get that gun? What the hell are you shooting at?” Glaring at me, he calmly slipped the pistol back into his pocket and said, “Spiny Lizard – missed it”. I was livid and horrified – which more I’m not sure. To pop off a few rounds way out in the thornforest was one thing, but in a village?

Possession of a gun in Mexico was in violation of both U.S. and Mexican law. The news of the time was a-plenty with tales of American citizens rotting in Mexican jails on weapons or merely ammunition possession charges. To have even a 22 caliber pistol round loaded with birdshot in your pocket meant real jail time in a Mexican prison. At very high volume, total seriousness, and, in great detail I tried explaining this to him, but he just smiled that exasperating smile of his and said, “Georgie (yes, to him I was always Georgie), you worry too much, don’t sweat the small shit.” SMALL SHIT…..SMALL SHIT!! Somehow I viewed the prospect of dealing with the Mexican judicial system as far more than small shit. To say that I was less than happy would understate the understatement.

That was my first and decidedly last trip with him into Mexico. His brand of craziness was just too much for me in a foreign land with foreign laws. International incidents with accompanying jail time in hell-hole prisons are just not my thing. I did, however, venture out with him on a number of trips into Arizona and New Mexico. Most of these, like the one at the opening of this essay, were on the lookout for one of Arizona’s most elusive snakes – the Milksnake, Lampropeltis triangulum.

Together over a series of extended field trips we traversed much of northwestern New Mexico and northern Arizona. We were not only looking for new specimens, but trying to pinpoint the exact historical localities of the first Milksnakes found in this area. With four-wheel drive vehicles and copies of ancient military maps, we followed, as best we could, the route taken by Captain George M. Wheeler and his 1873 Survey west of the 100th meridian from which H. W. Henshaw collected and H. C. Yarrow reported on the first Arizona specimen known.

Jim Higgs and George Bradley at camp near White Hills, Vekol Valley 26 April 1998. Photo by Chris Baptista.

It was on these field trips where I was privileged to absorb not only a fraction of Lowe’s encyclopedic knowledge of southwestern natural history, but his feeling of and feelings for these places as well. On occasion, as we drove along, he would suddenly say, “Pull over here Georgie.” He would then light a Roi-Tan cigar, walk off the road a bit, and sit either on a rock, log, or cross-legged on the ground and silently stare out over the landscape. After a while, sometimes a few minutes, sometimes and hour or more, he would simply stand up and say, “Let’s go Georgie, I’m working on the story here.” Afterward, as we drove on, he would expound upon the geology, grazing history, fire history, climate, and community structure of that place. I was in the best, the only, seat in the house for this lecture-gift. These moments went a long way toward mitigating the less than easy flip side of his personality.

Lowe and I made many trips into the vast ecological wonderland that is Arizona over the years. One of my fondest and most vivid memories of the man is when I took him to a Black-tailed Rattlesnake den that I knew of in central Arizona. I’ll never forget us hiking to the den’s opening early one April morning. Lowe, after determining which fissure the snakes would likely issue and where they would travel to sun themselves, sat himself smack dab right in front of that crevice and waited for their daily emergence. He was in his own heaven when they began to slowly crawl out and across his feet as he sat there quietly taking notes and puffing on his Roi-Tan stogies. The snakes seemed to ignore him and treat him as so much hillside as they exposed themselves to the warming rays of the sun as they have done for eons. With his dirty khaki clothes and straw hat, he blended in perfectly with the rocky hillside, becoming part of that landscape – even to me as I stood only yards away.

Sure there were times I had to talk myself out of punching him, but those other times, those other moments in which he helped me see what I had been blind too, those times he provided me the opportunity to make a living doing that which I most wanted to do, those times that I was personally tutored by my friend – The Dean of American Desert Ecologists, yes, those times overshadowed that craziness. These days when I think of Chuck Lowe, I think little of the belligerence, paranoia, or overbearance, but rather the stogie-smoking character who knew of nothing better in life than being surrounded by and covered in rattlesnakes as they experience their spring emergence from hibernation.

George Bradley