Charles H. Lowe Remembered

David E. Brown

August 30, 2016

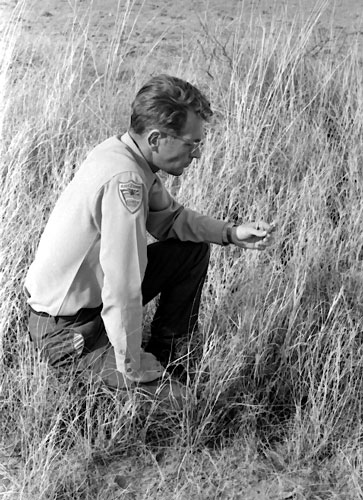

David Brown, 2016, Wild Horse Reservoir, Nevada

I well remember my first encounter with Dr. Charles H. Lowe, Jr. It was 1964, and I was a Wildlife Manager in Tucson mapping the vegetation of my game management unit. Wondering why ironwood trees were found off Orange Grove Road and not Ina Road, I posed the question to a colleague, Mike Halloran, who had just graduated from the University of Arizona.

“I don’t know the answer he said, but I know who does. His name is Dr. Lowe and he knows all there is to know about the Sonoran Desert.”

An hour later we were in Lowe’s office, where I again posed my question. The answer he said was Liebig’s Law of the Minimum, which he restated as meaning that the distribution of living plants is controlled by either minimum temperatures or minimum available moisture.

“The Tortolita Mountains are higher in elevation and too cold for ironwoods, which are tropical trees. That is also why ironwoods are confined to drainages when you get into the drier creosote dominated areas – that is where the most moisture is.”.

My epiphany complete, he marched me over to the “Tower,” where the University of Arizona Press and Marshall Thompson’s office were located. Entering the storeroom, he pulled out a small lime green book, made a correction to a literature citation for Walter P. Taylor, and thrust it in my hands. I am today looking at this book, The Vertebrates of Arizona in front of me.

“This is what you need to know to map vegetation,” he said, paying no attention to my offer to pay for the book.

That night I read “Vertebrates” from cover to cover, and then read it again, taking notes wherever I had questions. These I presented to Lowe in his office the following day. Looking somewhat amazed that someone had studied his book so intently, he answered all my queries in what was one of the most poignant and intriguing lectures I ever heard. He couldn’t believe that a “wildlifer” would ask the right questions. I could not believe that someone else cared about such things. We became colleagues in a relationship that would last a dozen years. Although I was never formally one of Lowe’s graduate students, he was my academic mentor just the same. He expanded my horizons on trips throughout Arizona, ventures into the Chihuahuan Desert, an expedition that crossed the Sierra Madre, and a search for palms from the Hieroglyphic Mountains to the Colorado River. I became good friends with some of his graduate students like John Phelps and Mike Robinson. Most importantly, Lowe and I became partners in a biotic community venture that would result in a classification system, a book and a map of the Southwest and Northwest Mexico. No one knew vegetation and reptiles more than Chuck Lowe. Trained in biogeography at San Jose State, I was the contributor when it came to birds, mammals and landscapes.

David Brown, 1962, Arizona Game and Fish, Tucson office

Working with the “Chief” was an adventure. He could be charming and cutting in the same sentence, and his personality was often outrageous. Getting him to share his true thoughts required tact as he could be manipulative and often had hidden agendas. Field trips were spent following his orders and depended solely on my equipment and expertise as Lowe avoided any modicum of preparedness. I much preferred camping out with Ray Turner and my other colleagues – something that rankled, but did not change him. Still, no trip with C. H. Lowe would ever be forgotten. He was if anything, the most memorable man I ever met.

He was a big man (6’4”) and everything about him was out of proportion including his intellect. His behavior, while often outrageous, was also backed up by being absolutely fearless. No official was too powerful not to be dressed down in public, and I once saw him attempt to wade with near fatal consequences across a flood-swollen Verde River. He always put on a great show, and having been raised in Hollywood, knew how to get attention. He was insightful and quick, and I much valued his insights. He was also generous, giving me senior authorship of our projects as long as I followed his rule and worked up the first and final drafts.

David Brown, 1970, Masked Bobwhite release, Sasabe, Arizona

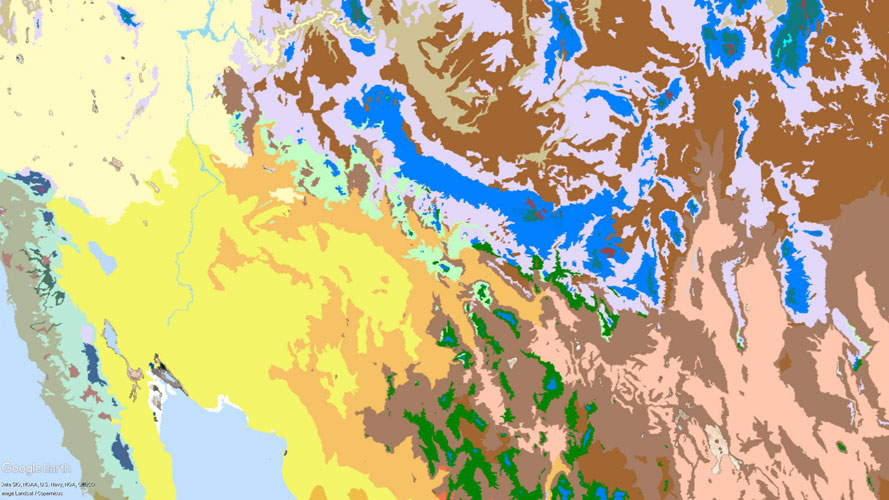

Our primary venture was a map and book incorporating a digitized classification system for the biotic communities of the Southwest, the boundaries of which he had already determined. I was to generate the map and we would divide the chapters among ourselves and other authors. When the University of Arizona Press turned Lowe’s query down, I sought out the U. S. Forest Service as a publisher. The Forest Service’s Charlie Pase would do chapters on chaparral and woodlands.

But nothing in Lowe’s world was now easy, and such was the fate of our book. The Chief was increasingly beset by personal demons and warned that “bad times” were coming. His behavior became erratic and the promised chapters never materialized. Every week saw new digressions and I suspected chemical interference. When I finally did coax the one chapter he wanted to do above all others – the one on the tropical deciduous forest-- it was an incoherent rant. Charles H. Lowe, for whatever reason, had lost his ability to write.

He told me that the bad times had now come and that he was dropping out. Natural history still interested him but his plate was now too full to work on our projects. I told him that I would finish the book as so much energy had gone into it –energy that he had done so much to instill. But he was disconsolate and only glared at me. I gave the book to Frank Crosswhite to publish in Desert Plants. Our working as a team had run its course.

I saw the Chief one more time due to the encouragement of Russell Davis. Lowe was in a rest home but still driving and we went to his favorite restaurant on Stone Avenue. Our dinner was cordial but such subjects as ironwoods never came up. We both left dissatisfied, realizing that an end of an era had come to pass.

I still think often of Dr. Lowe and hardly a day goes by that one of those days in the 1960s and 70s do not again come forth. The Chief was a big part of my life and I miss not being able to visit him in his “Gloyd Memorial Laboratory. Sometimes, when passing Room 100 in the old East Wing of the Biological Sciences Building, I think I smell cigar smoke. When I do, I have to suppress an urge to knock on his door and see if he is in and wants to talk about ironwoods.

Brown and Lowe vegetation communities map, 1980