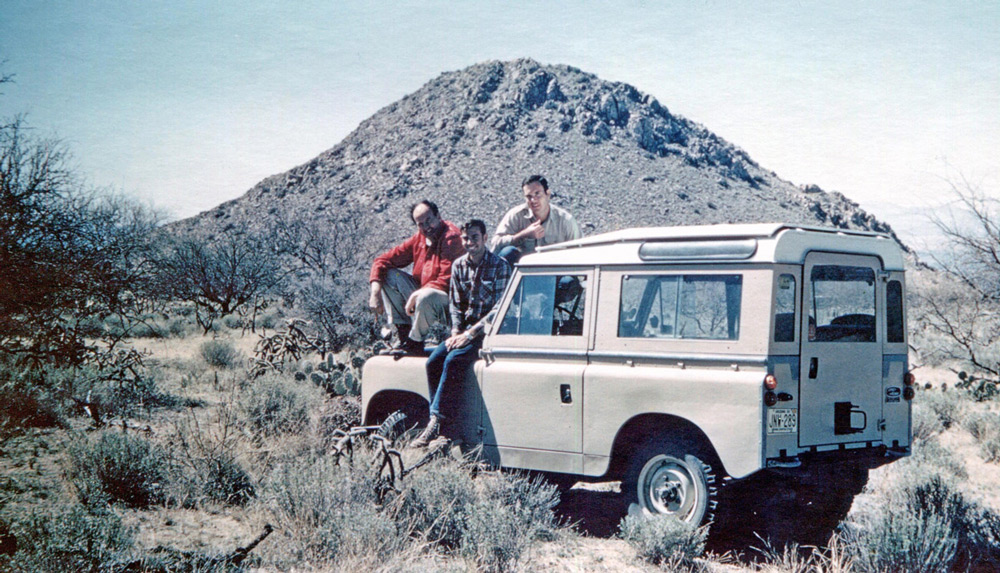

Huerfano, 1966

Chuck Lowe (left), Robert Bezy, and Mike Robinson on Mike’s Land Rover at Huerfano Butte, Arizona. Photo by Jay Cole.

By Robert L. Bezy

Robert Bezy, 2017 La Poza Grande, Baja California Sur, photo by Kathleen Bezy

On the afternoon of 1 July 1966 I left Tucson in my Scout and drove to the Santa Rita Experimental Range to visit Dave Hinds. He was camped there studying the comparative physiology and ecology of Lepus californicus (Black-tailed Jackrabbits) and L. alleni (Antelope Jackrabbits ). Even under the speckled shade of a large mesquite, the afternoon was hot, and we decided to wait until the morning to go lizard collecting. When the sun finally went down, I opened my can of Dinty Moore beef stew and held it with tongs over the weak flame of a can of Sterno. It was only lukewarm when I managed to spoon it down without gagging.

Dave and I got up before dawn, and I had my usual concoction of instant coffee, sugar, and cold water. We left camp at 6:45 a.m., stopping to help a kid whose truck was out of gas and stalled in the middle of the road. Our main target was Huerfano Butte. For years I had been puzzled by this hill and wondered what species of lizards it might harbor since, as suggested by its name, it is isolated from the main block of the Santa Rita Mountains. In the mesquite flats around the base we found many Aspidoscelis tigris (Tiger Whiptail lizards, a bisexual species). Climbing up the south slope of the butte we came to a small rocky area with A. sonorae (Sonoran Spotted Whiptail lizards) and A. uniparens (Desert Grassland Whiptail lizards), both of which are all-female species. One of the individuals we obtained had a color pattern resembling A. sonorae, but with some features of A. tigris. I turned the lizard over and pressed the base of the tail. Out popped two hemipenes. Was it a hybrid, as it appeared to me, or was it a "rare male" in a unisexual species, as some herpetologists imagined to exist?

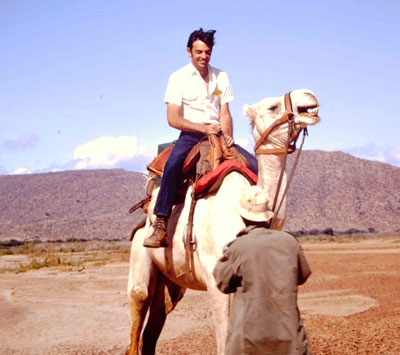

Robert Bezy, 1971 Samburu District, Kenya

We continued our lizard hunt, visiting four other sites between Huerfano and the Santa Ritas. Afterwards, we went up to Mike Jaeger's house in Florida Canyon where I called Charles Lowe and told him about the discovery. I explained that all the specimens were preserved. "Bobby, do you have a sleeping bag out there with you?" "Yes, I do." "Then don't come back until you get a live hybrid for karyotype analysis." I invited him to come out and join in the effort.

At 7 a.m. the following morning Eldon Braun, Annette Halpern, and Oscar Soule arrived and all five of us went up to Huerfano Butte. During the morning we managed to secure live individuals of the putative hybrid plus the potential parental species. We had succeeded in getting the lizards from which Jay Cole would obtain the chromosome preparations to determine whether the lizard was actually a hybrid and, if so, what the parental species were.

I returned to the lab rather smug over our success. At my desk later that night I was perusing my copy of Lowe and Zweifel’s 1952 original description of Cnemidophorus neomexicanus (now Aspidoscelis neomexicana), the paper that had convinced me in high school to attend the University of Arizona and work with Lowe. He arrived in the lab and asked what I was reading, and I proudly showed him the paper. He accused me of having stolen the reprint from him.

I was furious, slammed out the back door, drove home, and dug out the price list from Quivira Specialty Company (Charles E. Burt, proprietor) on which I had checked the reprint for ordering many years before. Driving up to the back of the Biology Building, I found Lowe leaning on the rail of the back porch and smoking his Roi Tan cigar. I threw the order form at him, "Here's the evidence that I purchased that reprint before I came to the university." "That doesn't prove a damn thing, it’s just some old list," he retorted. A cop drove up and said he had clocked me doing 45 mph on campus. Lowe yelled down to him, "Throw his ass in jail, that's where he belongs.” All is fair in love, war, and herpetology.

Apidoscelis tigris (Tiger Whiptail lizard). Photo by Kathryn Bolles.