From the Bronx to the Baboquivaris (with a stop at Three Points): the Steve Goldberg Story

My career in zoology began in 1946 when my parents purchased a summer cottage near Peeksill, New York. I could not get over the frogs I encountered. They opened the door of nature study for me. On future trips I would venture into the eastern deciduous forest where I got "high" on the smells, animals, plants, etc. I remember the metallic blue of the damsel flies, the bright orange red efts, the "ghostly" indian pipes on the forest floor. Back in the Bronx, I made weekly trips to the American Museum of Natural History on Central Park West. I stayed with nature my entire youth. In the 4th grade my teacher (Mrs Chodosh) put me in the back of the room each afternoon. Not for bad behavior; she let me copy from an old bird book. I was intrigued by extinct birds like the passenger pigeon and Labrador duck, even though I did not understand the taxonomic features I was copying; tarsus, metatarsus, etc.

Stephen Goldberg and his roadrunner, ca 1968, University of Arizona

I arrived at the University of Arizona in January 1963, having visited there the previous August. I had a gut feeling back then, that is where I belonged. Unfortunately, my parents prevailed on me to stay closer to home. I spent the fall semester 1962 at Temple University, Philadelphia, PA. The biology at Temple was all cellular which was not for me. I had previously been admitted to the University of Arizona. One afternoon as I gazed outside at the bleak tenements of North Philadelphia, I decided to call the University of Arizona and see if they would still take me. Much to my surprise, they said yes. Things were set into motion and I headed west. I arrived in Tucson, spent a few days at the Santa Rita Hotel and headed for the university. I had looked at the curriculum in animal biology at U of A and figured with work in all fields of organismic zoology, I could find something to do. On my arrival. I was given the unpleasant news that my admission was a mistake. My undergraduate grades were not good enough to meet the U of A standards! Well I was there so would do my best.

Lets face it, I needed help. I was a lost soul in the wild west! After all, I grew up a few blocks from Yankee Stadium, Bronx, New York and was not prepared for life in Tucson. I would carry all my books in an oversized blue book bag, appeared utterly defenseless and made an inviting target to the "rough and tumble" graduate students.

I needed to select a major professor and a research project. My first experience was with the mammalogist, E. Lendell Cockrum, who was looking for somebody who would do a mammal survey on a military site. He said the roads were in terrible condition and I would need a four wheel drive vehicle. I assured him I could do it as the used car I purchased had four wheels. Well, what do you expect from a kid from the Bronx who could not even drive? In the Bronx, most folks, including me, travelled by subway. As an aside, Dr. Cockrum and I later became good friends.

One day, I wandered into the back room of the Lowe lab and was amazed to see so many preserved herps. I started to consider working in herpetology. However, the word in the halls about Dr. Lowe was that he "played with personality" and should be avoided.

One learning experience was my trip with John Wright into the mountains of Sonora, Mexico. We were after Cnemidophorus [now Aspidoscelis]. We traveled in John's truck on four bald tires. Talk about a contrast with the Bronx!! The thorn forest was hot and dry. Sitting in the shade, my body was covered with sweat. I remember crawling under a fence, only to be chased by a bull.. I was impressed by how devoted a son John Wright was. No matter how busy John was, he would always take out time to write a letter home. Late in the day, John and I went into town and visited a home. I really enjoyed meeting the sweet Mexican girls that lived there. Seemed John was always looking out for me! John was an expert field person. He used rubber bands to collect lizards. I recall an instance when John brought the truck to an abrupt halt. He had spied a mud turtle in a pond off the road. Talk about sharp eyes! John then scaled the fence, shot the turtle in the eye, with his pistol, waded into the pond and fetched the turtle. It sits in UAZ today as UAZ 27958, Kinosternon flavescens [= K. stejnegeri], coll. 8/10/63, 9.7 mi (rd) W Tecoripa, Sonora, Mexico. That was the only trip I took with John.

Seemed I could do nothing right. In Lowe's Ecology class we took a November trip near Kingman where we spent a very cold night. I observed Pete Lardner brushing his teeth and informed him that John Wright did not brush his teeth in the field! Unfortunately it went viral and came back to haunt me. Making things worse, I let one of Bezy's Xantusia escape. I also had a frustrating time in his Advanced Herpetology class. All the graduate student gurus would take it and you could repeat it for credit. I knew I needed to participate as there were no written exams. Still, it was hard for me to speak in class. Finally, I blurted out "I have a case of...." Lowe retorted and I have a case of. This brought the house down. I was so humiliated.

I got to know the young Lowe family when I baby sat for Dr. Lowe's two children, Cal and Cathy. I remember driving the terrible road on Sweetwater Drive to reach the Lowe household. There I met his charming wife, Arlene. She was a tall, outgoing, friendly grade school teacher with a warm and wonderful smile. I always made some purchases from Cathy's Rock Shop. Somehow, I cannot recall Dr. Lowe paying me.

Yarrow's Spiny Lizard, Sceloporus jarrovii, photo by Ana Lilia Reina-Guerrero

I might have a chance to join the Lowe Lab. Turned out that the late Ken Asplund had decided to continue his doctorate studies at the University of California Los Angeles. This left an opening for a person to do reproductive histology. That sounded good to me as I had done well in Histology and enjoyed the solitary work involved in studying slides. Ken taught me how to prepare histology slides and found a place for me to work in the basement. So the deal was done. I would do a reproductive study on Cnemidophorus tigris [now Aspidoscelis tigris] for a M.S. degree. I bought a 22 pistol and a box of 50 bird shot shells and drove my Fairlane Ford to the wilds at the North end of Campbell Avenue, north of Tucson. The lizards were thick, but I used all 50 shells without hitting one. I returned the next day and managed to shoot one in the leg. That launched my career in reproductive histology.

Enigma: The most frustrating behavior of Charles H. Lowe was his inability or lack of interest in completing works. This was tragic as many of these were important works that never saw the light of day. It was indeed striking as he would push himself and others to the breaking point and then seemingly lose interest and move to another project. He would stay in the laboratory for days, never showered, shaved or exercised and lived on candy bars. I reviewed several of his unfinished projects and they were magnificent. He often would find a minor glitch which caused him to tear up pages and begin again. I am amazed he lived as long as he did with this frequent destructive behavior. A number of people lost major projects as a result of Lowe’s irrational doings.

Where do I fit into the above? In the mid 1960s I was involved in such a project with Dr. Lowe. It was a detailed description of the testicular cycle of Sceloporus jarrovii to be published in the Journal of Morphology. We finished it in August 1966. He then drove me to the airport as I was going home to New York. He promised we would submit the paper. On my return from New York, I never saw the paper again. The word had gone out, if Goldberg mentions the jarrovii paper once, he is through. All of a sudden I had become persona non grata and my road toward gaining the Ph.D. would be littered with boulders. It was clear that during my short visit to New York, Lowe had lost all interest in me.

Yet I remember my days in the Lowe laboratory with fondness. There was a great cast of characters and they all performed to the lead of the maestro. Lowe was fond of giving people nicknames, I was little Steve and who can forget, Big Al from Kokimo, Alfred Lunt Gardner. One graduate student kept a live duck in his apartment! Lowe even had his own language, "fat rat, hogan, how how." Those were welcome words as Lowe used them only when he was in a good mood.

Lowe, on my behalf, wished for me to overcome my acute shyness. With this in mind, he insisted I get a roommate. Thus I spent one year with a graduate student in an apartment on Ninth Street in Tucson. Lowe made many cutting remarks like, “I gave the roadrunner to Goldberg as it was the only friend he had.” He also spread stories about me being chased by a bear on Mt. Graham. Did he really think I was dishonest? Then, why?: “Goldberg, if it’s the last thing I do, I’ll make an honest man out of you.” Lowe could switch from being a jovial, fun person spewing words of wisdom to a brutal, nasty character. The trick was to watch his eyes. If they moved in a certain way and his lips puckered, batten down the hatches, a noreasterner was coming. He was not above sending two students that did not get along on a collecting trip. Seemed to enjoy hearing about the fireworks on their return.

One nice experience I had at U of A was counting Agkistrodon scales for Howard Gloyd. He was a kind gentleman and served on my Ph.D. committee. His disposition was the opposite of.....

It is true that Lowe refused to process my dissertation even though it was done. Lowe had in his mind a sequence of students to finish and I had to wait for the others to pass me.

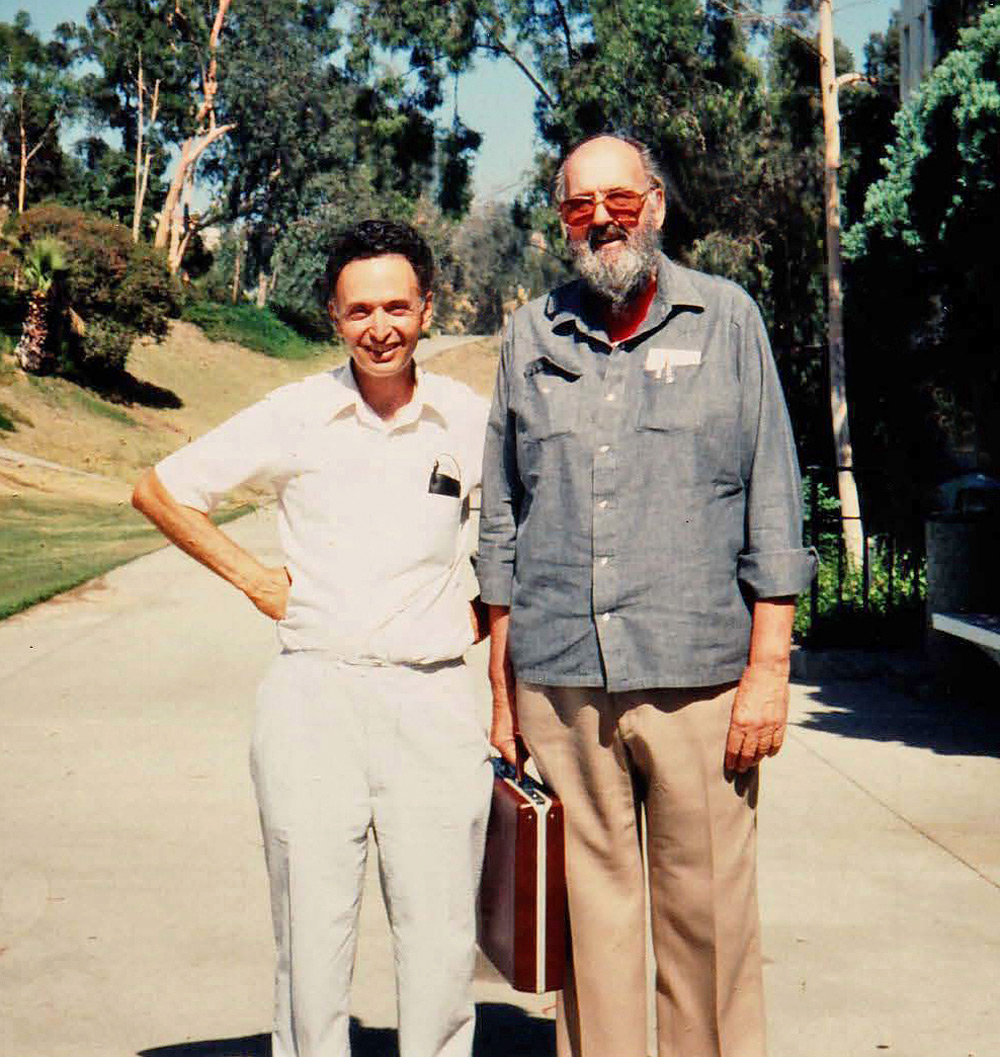

Stephen Goldberg (left) and Charles Lowe, 1989, Whittier College

When I finally passed my Ph.D. orals, I loaded my car and was ready to drive to Whittier. Before I could turn the ignition on, Lowe stormed from the Bio. Sci. building. He thought I was leaving Tucson with his manuscripts and histology slides. I was exhausted and in no mood to fight an angry bear. I let him take what he wanted as a price for my freedom.

Happily we reconciled after I left moved to Whittier in March 1970. He actually visited me at Whittier in 1999 to finish our long lost paper on Heloderma reproduction. I made occasional Tucson visits to pull gonads from the UAZ collection. Dr. Lowe was living in an apartment on Helen Street. I would bring him lunch; he was partial to deli meat sandwiches. A jovial lady named Rosie looked after him. On one occasion I opened his fridge which contained only cartons of ice cream, chocolate or chocolate chip as I recall. Rosie made sure he would take the various pills he was prescribed. Unfortunately Lowe had problems with the U of A sending him retirement checks in a timely manner. I willingly "loaned" him money each time I visited him.

In closing, the truth is Dr. Lowe gave me a lot. My early days in the Lowe lab were wonderful. He gave me the gift of the Sonoran desert in the spring of 1963. How can I forget the flaming ocotillos, the shrill sound of the cicadas, the smell of creosote and the bright blue Tucson sky. I recall his herpetology class where he gave each student a Raleigh tobacco tin to place collected herps in. I remember the incredible beauty of Coleonyx, and seeing my first Gila Monster. Lowe was the real deal, no political correctness here. I learned so much from him. His love for the desert and biota was inspirational. Could you believe he said, "If you would not die for herpetology, you don't belong in it." Above all, Dr. Lowe gave me something nobody else could or would have given me. Sometimes I wonder if he did it to piss people off as he loved to play with personalities? I’ll never know, why he did it, but then the tears come as I think, he must have sensed something good in me that caused him to open the door and give me the chance to do something useful with my life. For this, despite the gale force winds and stormy seas, I will always cherish my memories of Chuck Lowe with deep love and admiration.