Adventures with Lowe - In the Lowe Lab, August 1977-May 1981

Frank Reichenbacher

Paradise

I grew up in Paradise Valley, Arizona. Home was a creosotebush flat near Mummy Mountain. I was catching lizards, snakes, tarantulas, round-tailed ground squirrels, many kinds of ants, butterflies, toads, and more before I hit 10.

One day we were out in the backyard playing baseball. Someone hit the ball hard and my little brother ran to fetch it. We watched him chase it. At one point he jumped high in the air for no apparent reason. When he came back we asked him why he jumped and he said, “Oh, there’s a rattlesnake!” We ran to go see it. It was a small, maybe 30 cm long, Western Diamondback. I ran into the house and found something to put it in. Using a baseball bat and sticks I coaxed into an Erlenmeyer flask from my chemistry set.

I was a science nerd. No doubt about it. In high school I became very involved with the new environmental movement through the Saguaro Ecology Club.

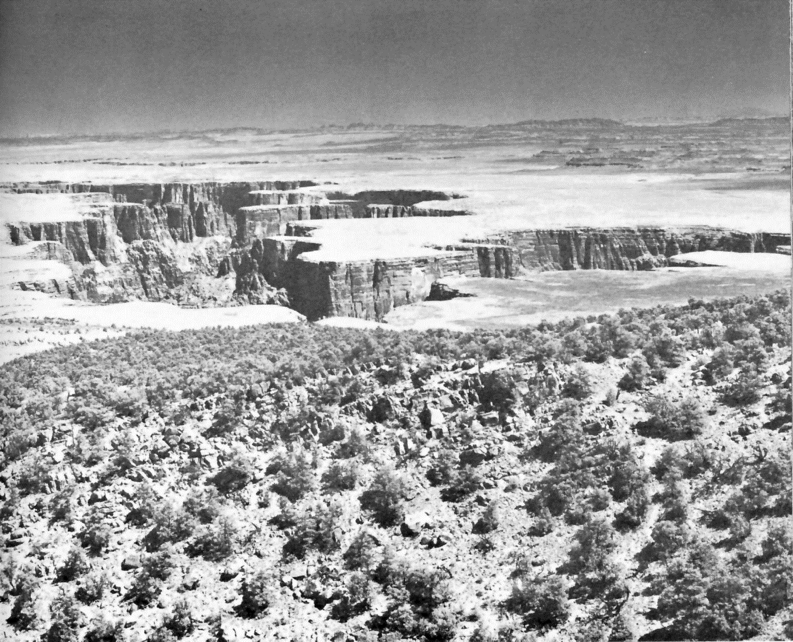

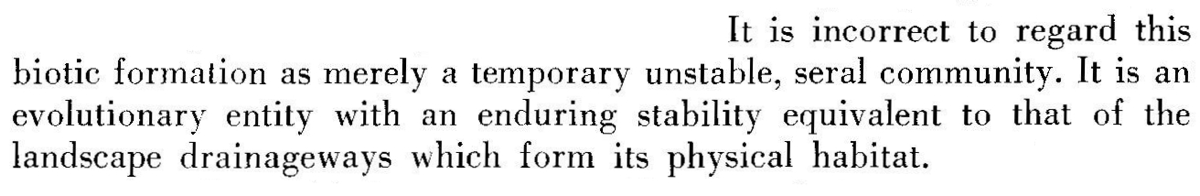

Page 59, Fig. 39, Vertebrates of Arizona

Some friends and I from the Ecology Club traveled to the Shivwits Plateau on the Arizona Strip. In a rickety pickup truck and one or two sedans, we drove up to St. George, Utah, from Scottsdale and then south all the way to Mt. Dellenbaugh, an extinct volcano perched on the Kaibab Limestone right at the edge of the Grand Canyon. Not coincidentally I had a book with me written by the mountain’s namesake, Frederick S. Dellenbaugh. He had accompanied John Wesley Powell on his second trip through the Grand Canyon (1871-1872) and he wrote about it in “The Romance of the Colorado River.” He was 17 at the start of the float.

I was 17 years old too as I read “Romance” on the edge of the Grand Canyon one hundred miles by dirt road from the nearest town.

I had another book with me titled, “The Vertebrates of Arizona,” by Charles H. Lowe, Jr. Page 59, Tad Nichol’s beautifully composed picture taken from the east slopes of the Kaibab Plateau looking northeast across the Little Colorado River gorge.

I remember me and my friend Tom Wright standing on the canyon rim holding the book up to the vista spread before us looking north from Dellenbaugh toward the Virgin Mountains. We saw that crisp, arid landscape stretching before us in every direction as far as we could see with no human influence visible anywhere.

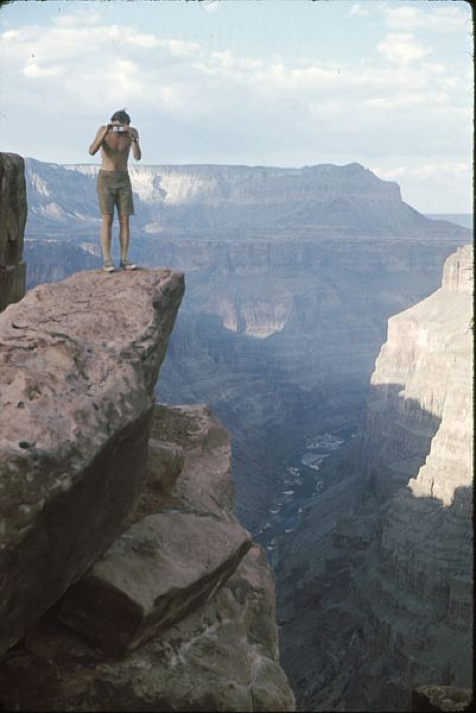

Tom Wright at Tuweap Overlook (F. Reichenbacher)

I remember me and my friend Tom Wright standing on the canyon rim holding the book up to the vista spread before us looking north from Dellenbaugh toward the Virgin Mountains. We saw that crisp, arid landscape stretching before us in every direction as far as we could see with no human influence visible anywhere.

How I got there

Having graduated from the Prescott Center for Alternative Education (successor to the bankrupt Prescott College), I found my way to the Herpetology Lab of Charles H. Lowe, Jr., at the University of Arizona. This was no coincidence. While in Prescott my mentors were Ken Asplund, Maggie Fusari, Carl Tomoff, and Ken Kingsley. Ken Asplund, Maggie, and Carl were well acquainted with Lowe.

Graduating from a hippie school whose founding principle was something called “experiential education,” I really had no idea what I was getting into. I was apparently going to have to experience it.

You would think my close association with my mentors would have given me a clue, but that was not the case. I had no idea how universities worked, or what if anything was different about advanced and undergraduate degree programs and how Lowe fit into all that. I did not know what an academic advisor was or how this person interacted with a graduate student. Until the moment I enrolled I did not know that I needed to do anything other than enroll. So I was an unclassified graduate student for a full year.

But Lowe took me in and with bluff, bluster, intimidation, and persistence, I was admitted to the program as a Master’s candidate in 1978. Later, the graduate school did away with the unclassified graduate student because of the trouble Lowe and I created for the University Politburo.

Natural history and cigars

Garcia Y Vega in a box

Before the Aravaipa Canyon field trip Lowe told us there’s just three things.

“Bring ‘em back alive!"

“Don’t let ‘em fuck in the bushes.”

“Try to teach ‘em something.”

The ever present cigar was a Garcia y Vega, which came in brown plastic tubes. Sometimes he would send me in to a drug store or grocery store when we were on the road to pick up a couple.

Barry Spicer told me once that the combination of two aromas signaled an approaching Lowe: Cigar smoke and little farts.

I was never lost, part I

Terry Johnson, Cecil Schwalbe, and I drove out to the Mohawk Dunes to set up camp in advance of Lowe’s Herpetology field trip crew. It was one of the first warm days of the year. We set up camp and then Terry and Cecil drove off somewhere while I walked across the dunes to the east all the way to the Mohawk Mountains. I was wearing a hat, a T-shirt, a pair of pants, and flip flops. I had a little less than a quart of water.

Have you ever heard of the Mohawk Dunes? No? That’s not surprising. They don’t look much like the sand dunes you see in the movies being mostly stabilized by vegetation. Not only that, but the dunes are in the U.S. Marine Air Corps Gunnery Range and access requires special permission. Otherwise you may find your peaceful desert sojourn interrupted by low-flying heavily armed jet aircraft flown by young men and women just itching to blow something up.

The vegetation on the dunes is actually a feature that makes them especially attractive and fruitful for herpetological research. Vegetation plus sand creates habitat for many desert and dune adapted reptiles which are rare or absent from much of the rest of the Sonoran Desert. The barren, wind-blown sands you might usually envision in sand dunes can provide habitat for only a sprinkling of strictly dune-adapted organisms (both plants and animals). Not very much there to really study.

Let’s take a look at the Mohawk Dunes first, before we get too much further into our adventure story.

The Mohawk Mountains (F. Reichenbacher)

I was never lost, part II

The Mohawk Dunes appear to be a composite dune system created by sand carried southeast from the nearby Gila River Valley on northwesterlies blowing around the back sides of mostly dry winter storms. Sand blowing up the Mohawk Valley from the northwest is then sorted by the prevailing winds, which in southern Arizona are always from the southwest.

The two opposed wind patterns create an interesting pattern in the dune with somewhat rectangular swales (I used to call them blow-outs) honeycombing the dune system.

The dunes are old. The swales, especially, are replete with bits of fossil bones. Some large, some small, and the lithic debris left behind by Native American hunter gatherers. Stabilization of the dunes by woody vegetation indicates that the system is no longer obtaining sand from the Gila River. The extent of re-vegetation hints that the machinery shut down well before the valley was transformed by Americans into an agricultural heaven.

The Mohawk Dunes are a very linear system, more than 30 km long, northwest to southeast, and two to four kilometers wide, southwest to northeast. Lowe typically established the Herpetology field trip camp on the west side of the dunes about 15-25 km south of Interstate 8. Motor vehicle access is relatively simple, if one keeps in mind that the whole valley is very sandy, and the closer you get to the dunes, the more treacherous it becomes.

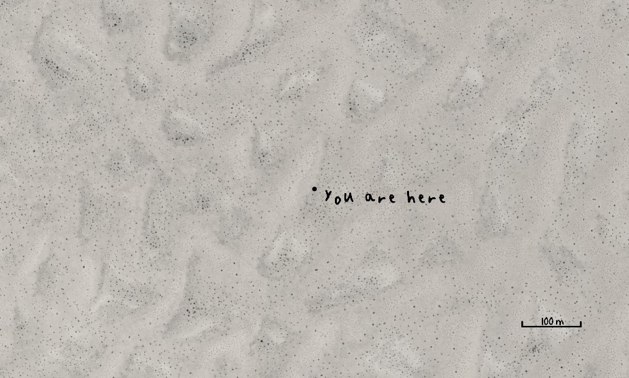

You are here!

I was never lost, part III

As I was saying... Terry, Cecil and I arrived early and set up camp in the usual place. I took off east across the dunes heading toward the Mohawk Mts. From every ridge in the dunes you can look to the north and east and easily see your landmarks, Interstate Highway 8 and the Mohawk Mts. The town of Tacna is only a few kilometers away.

So I trudged across the dunes as the day grew warmer and warmer. Yuma recorded a high temperature of 37.2ºC that day.

The mountain was great. No herps to speak of, but I wasn’t really there for herps. I was, however, completely out of water and it was time to head back.

I became aware of a small problem as I approached the dune system again from the east. I started to realize that if I didn’t hit the dunes at the right place I was not going to find my tracks to follow back to camp. I arrived at the dune ridge and could not find my tracks. I was wasting time and I was out of water. So I figured, “Heck, I’ll find camp. How hard could it be?”

Turned out to be a real stinker of a problem. I got to the west side of the dunes and camp was nowhere to be seen. Am I north of camp, or south? Do I turn right and head north, or do I turn left and walk south? Hmm... Oh well, I’ll go south for a way and if I don’t find camp, then, I’ll go north. How hard could it be?

I was never lost, part IV

I walked south in the growing heat. Trudging along in my flip flops. I walked for what seemed like hours. There was no camp and I could tell that the dune system was sweeping to the east toward the south end of the Mohawk Mts. I had gone too far south.

Obviously I had to turn around and walk north. And so I did. I walked and walked and walked. As I walked I became aware of a small problem. I had no way to know where my turn south point was from earlier unless I happened to stumble right on to my foot prints. I would have no way to know if I had overshot my point. Well, hmmm...I didn’t have much choice in the matter, did I? I continued north.

Walk on the Mohawk Dunes

And I walked and I walked and I walked. I walked north so far I became convinced that I had far overshot myself. That meant camp was somewhere behind me to the south. Maybe I had walked right by it and I happened to be just below the opposite side of a ridge. But camp was not in the dunes, it was in the flats adjacent to the western margin of the dunes. Or was it? So I turned around again and I trudged south.

And I walked.

And I walked.

And I walked.

It turned to late afternoon. The straps on my flip-flops were abrading the webspace between my first and second toes and I was leaving a little trail of blood drops.

Sometimes I had to stop and lie down in the shade of a creosotebush. I actually napped. This was heat exhaustion, of course.

Late afternoon turned to night and still I walked. North to south and back again. I became aware of something just as the last light of day faded in the west. No, it wasn’t another small problem. Or at least I didn’t think it was.

I was never lost, part V

It was three sets of headlights in the north. Not headlights on I-8, which were visible, but a considerable distance away. These headlights were on the Mohawk Valley Road which was about two km west of me. It had to be Lowe and the Herpetology crew. I stopped and watched, eagerly anticipating that they would shortly make a sharp turn to the east and lead me straight to camp.

The headlights came closer and closer and closer and then, they went by me. Right past me. And they didn’t stop for quite a while. Either it wasn’t Lowe and the crew, or they were having the same problem I was.

Shit. Pretty soon I saw headlights veering wildly and engines gunning. Then everything stopped. In the still desert air, I could easily hear bellowing and doors slamming. Then more engines gunning while the lights bounced up and down crazily. Clouds of dust rose. Then, all was silent again. The lights stayed on for a while then went off and I could just make out the light of a wooden match and the flame of a freshly lit cigar.

I was never lost, part VI

But huzzah! I looked to the north and what should I behold, but the light of a lantern in the dunes. I had found camp! At last. And I was only about a kilometer away.

Heat exhaustion vanished in the evening cool. I reshouldered my pack and walked north one last time. Terry and Cecil were gone (Where could they be?) but all the equipment was there. I broke out a couple of quarts of Gatorade and drained them. Ahhhh. That was good. I felt great. Yeah, Lowe and the rest of them were in a terrible mess, but there was nothing I could do.

I got a little bored. Then I broke open my bottle of Hiram Walker’s Peach Flavored Brandy and pretty soon I felt really great. I mean really great. I was in love with the desert, and Terry and Cecil, God Bless them. They were probably worried shitless and out looking for me while I was sitting here just fine. Oh the irony.

Shortly, Terry and Cecil drove up. Everything was well again, although they both wanted to kill me. Lowe and the crew were eventually rescued but at least one of the vehicles was shot. And they all went back to Tucson. No field trip.

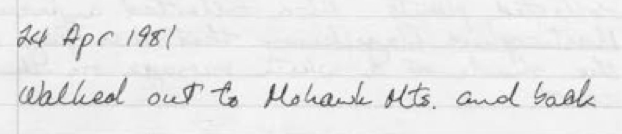

Here is what I wrote in my Journal for April 24, 1981.

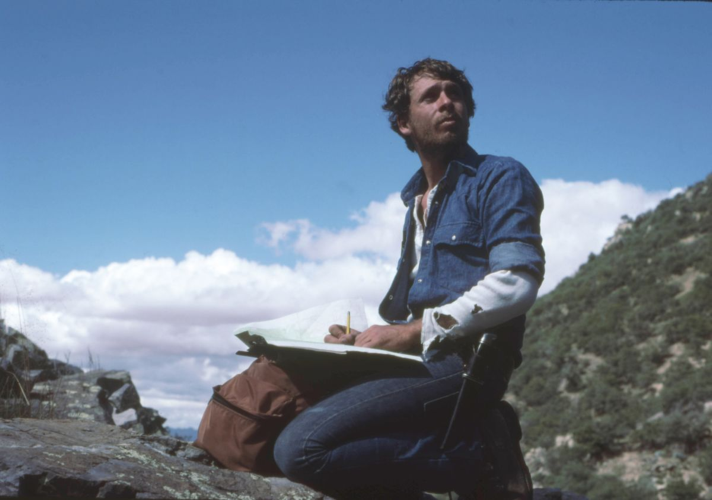

Me in Ramsey Canyon (Cecil Schwalbe)

Vegetation of Ramsey Canyon

Lowe wanted me to make a vegetation map of Ramsey Canyon. We spent a couple of evenings at the lab developing a project. I made two or three field trips out there and spent several nights and days in the field. My favorite trip was when Cecil Schwalbe dropped me off in upper Carr Canyon and I hiked down to Hamburg Mine, then up canyon to the Bear Creek Canyon divide. I walked all the way back down to the Ramsey Canyon Inn. I don’t remember how I got home.

I filled two or three plant press notebooks with vouchers. They’re all gone. Consumed in the conflagration that destroyed his home I assume. But I made the map and I still have it.

Me in Ramsey Canyon (Cecil Schwalbe)

Friends and colleagues

As is the case with many graduate students, my fellow grad students helped me get through it all. I remember one day I was particularly anxious and complaining to Barry Spicer. Barry always knew what to tell me.

Then there was Jim Hudnall. He was doing something with Massasaugas (Sistrurus catenatus). I don’t know whatever happened to Jim, but we went on several field trips, mostly for the Tucson Electric Power Co., Environmental Monitoring Program on the Four Corners Power Plant powerline project.

Jim Doidge and I went up to the Navajo Reservation EMP study site and sat in the car for a day waiting for it to stop raining. We drove back to Tucson bedraggled and discouraged. Lowe was furious we left the field after doing practically nothing.

The Santa Catalina Mountains

Lowe got me a little money to do a small project he had been thinking about for a while. He wanted me to hike up (or down) every canyon in the Santa Catalina Mountains and make a record of the lower and upper elevational limits of riparian trees and shrubs. I hiked Pima, Finger Rock, Ventana, Sabino, Sycamore, Bear, Soldier, and Molino canyons. Sabino was an overnighter. I camped in the pines without a tent and had the unnerving experience of trying not to move while a skunk explored my backpack for food. It made off with a salami.

I filled eight or nine plant press notebooks with vouchers. They’re all gone too.

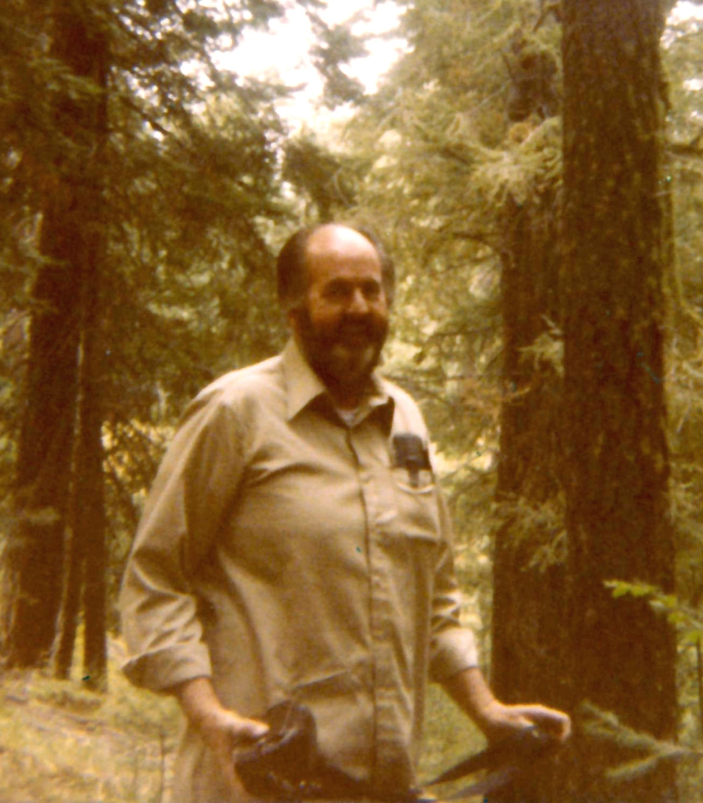

Lynn Bielsky at ORPI (F. Reichenbacher)

Butterflies

One day, after Lowe’s Natural History lecture (I was a TA) we were walking down the hall of Bio East together when a lovely young lady came around the corner. We both knew she was taking the class. Lowe immediately switched to charm mode. He took the cigar out of his mouth and shuffled over.

Towering over her, he looked down and said, “Hi honey.”

She beamed, looking almost straight up, “Hello Dr. Lowe.”

He puffed on his cigar and said, “How would you like to get paid to catch butterflies?” Wink, wink.

She squirmed a bit. Her name is Lynn Bielsky, she was from New Rochelle, New York, and she had only been a couple of months away from Northeastern Deciduous Forest. She said, “Ummm…”

Lowe was serious. He wanted butterflies for the Natural History lab and he was prepared to spend a few bucks. He gave her a net and turned her loose. In the next two or three weeks Lynn Bielsky collected zero butterflies.

That summer Lynn was my field assistant at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument on several field trips to redo some of the old saguaro plots. John Cross took us out and showed us what to do. We stayed at a house the Park Service used for visitors.

Crashing a Lowe lecture

Lynn roomed with Lari-Ann Clifford. They thought it would be fun for Lari-Ann to sit in on Lowe’s Natural History lecture, Room 100, Bio East, right across the hall from the lab.

Charles H. Lowe, Jr. (source unknown)

They sat in the front row together. Lowe was late. He came in the back and ambled down the central aisle. He was talking, lecturing, and carrying a cloth bag. Some of the more attentive students may have noticed the bag moved on its own. By the time he got to the lectern, the bag was open. He walked to the front of the lectern, reached in, pulled out a meter long Glossy Snake (Arizona elegans) and dropped it right in Lari-Ann’s lap.

Lari-Ann was recently from Wauwatosa, Wisconsin. She too, was in her first year outside of the Northeastern Deciduous Forest. Despite that Lari-Ann did not completely panic. She somewhat picked the snake up and offered it back to Dr. Lowe, “Here, uhhh, sorry I crashed your lecture.”

Lowe winked and said, “Oh that’s ok honey, stay if you want.” He smiled, put the snake back in the bag and continued with his lecture.

Next semester Lari-Ann happened to enroll in Mellor’s Organismic Biology course and I was her TA. Two years after that she and I started dating. We’re still married. Lari-Ann and Lynn are still BFF’s. We visit often.

Some form of telepathy

Lari-Ann graduated with her B.S. in 1981 and I got my M.S. at the same time. He was over at our house for some reason a couple of days after graduation. Lari-Ann mentioned that I had given her a book as a graduation gift. Lowe correctly guessed the title and author. I had not mentioned it in his presence and I do not think I mentioned it to anyone he knew either.

Fall rains

Lowe gathered me up and we went for a ride. I saw he had a camera, which I not seen him with before. We drove all the way to the Saguaro National Monument East Visitor’s Center. He didn’t tell me why.

It was a truly beautiful Tucson, Arizona, fall day. A storm had passed through and there had been rain. There had been rain a few days previous as well. We parked and he wandered out on one of the foot paths. I followed, trotting behind.

We came to a slight rock grotto. Club moss (Selaginella sp.) draped over granitoid outcrops. A few limberbush (Jatropha cardiophylla), cylindropuntias and platyopuntias of indeterminate species, foothills paloverde (Parkinsonia microphylla), saguaro (Cereus gigantea), and ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens) graced the scene.

He sat down on a rock and took the lens cap off the camera while puffing on a remnant cigar. I still had no idea why we were there. Not that there was no talking. We talked about everything except why we were there.

Charles H. Lowe, Jr. (source unknown)

I began to suspect something was afoot and that perhaps I was being tested in some way. He was more or less facing a young ocotillo growing on a rock among the club moss. It had about 5 cm of new growth at the tips of the four or five branches. I went up to it and looked more closely at this new growth. He said, “That’s it Frank, that’s it,” with a wry smile and another pull on the cigar.

Suddenly realizing that we were here because it was October and there had been rain and this was the Sonoran Desert, I knew. I knew about the contingency of life in the subtropics, and the frailty of desert life in general. It was a revelatory moment.

After a little while we drove back to the lab. I think about that every fall in Arizona and the insights I gleaned from it are with me still today. This year, for example. The Tumamoc globeberry population on Tumamoc Hill that I have been monitoring since 2007 (after a twelve year break from the 1990’s) produced the first significant crop of seedlings in at least ten years with very heavy rains in July. But August was a bust and September and October were almost completely dry. I am anxious to get out there next summer and see if any of the seedlings survived. If not it will have been because of the lack of fall rain. I am now wondering if fall rains are actually the key to Tumamoc globeberry survival in Arizona, and, furthermore, perhaps crucial to many other Sonoran Desert species.

EEB 483 herpetology

The event of the year was the field trip to the Mohawk Dunes in late April.

Lowe would normally bring a couple of cheap .22 caliber revolvers and a box of rat-shot loaded cartridges. Students would use them to collect lizards.

He gave a gun to an undergrad who we will call, “Gregg.” While Lowe and I sat under the shade canvas back at camp Gregg went lizard hunting. Every few minutes we heard, “Blam! blam! blam!” at all points of the compass.

Gregg came back an hour later having sacrificed no lizards for science and spent all his ammunition.

A year later we got a letter and photograph from Gregg. He’s sitting in the turret of an M60 Patton Tank at a U.S. Army base in Kentucky. Can’t miss your lizards with that!

Cecil Schwalbe and an anonymous rattlesnake

Snakes and rattlesnakes

Lari-Ann wandered into the lab one day looking for me. When you walked into the lab you had to bat your way through a curtain of sheets of paper scotch-taped to the door frame filled with phone messages for Dr. Lowe. That was the only way to make sure he actually saw them, otherwise it was plausibly deniable.

I wasn’t there that day, but Cecil Schwalbe was. He offered to show her his snake. Cecil was always offering to show his snake to the ladies.

Actually it turned out that Lari-Ann had wandered into the lab at an inconvenient moment as Cecil was in the process of putting up some live specimens. One of them was a rattlesnake in a cloth bag on the counter right next to Lari-Ann’s left elbow. Cecil was merely trying lure her away from the snake.

Standing on shoulders

He had me making copies of journal articles at the department copier. He came in while I was working on them and I started blathering about riparian deciduous forests and their ecology and evolution and my ideas, etc.

He stopped me and glowered, “You’re not the first one to go down that road, Frank.”

Indeed not. Every time I start to think maybe I might be smart, I think of that moment. In fact, his comments on the evolutionary unity of those communities in “Vertebrates,” drew me to his flame.

Twigs

As part of the Santa Catalina Mountains riparian canyon project Lowe spun off a winter key to the riparian trees and shrubs project for me. I photographed deciduous tree and shrub branches from fall through spring on an elevational gradient from Molino Canyon to Mount Lemmon summit. I used baling wire and stamped brass tags to permanently mark each tree and shrub.

Then I contracted with a young lady who lived in Polo Village to do line drawings of perennating buds: willows, walnuts, cherries, etc.

Years later I walked down to Molino Canyon from the highway and spent an hour trying to get my wire off a willow tree trunk. The trunk was becoming disfigured from the constriction. I felt horrible, but there was nothing I could do. I gave up.

Lari-Ann Clifford (F. Reichenbacher)

The drawings and the plant press notebooks are gone. I still have my journal notes.

Momma

Two years after I graduated and was working for the Arizona Nature Conservancy we met Lowe for lunch one day.

He looked at Lari-Ann and said, “Hi Momma.” He called her ‘Momma’ several times. Lari-Ann thought he’d simply forgotten her name.

A couple of weeks later we learned that Lari-Ann was pregnant with our first child.

$****

The money from the little projects Lowe found for me got me through many tough times. One fall I got a check from the UA for $****. Literally, I had a check for four asterisks. It did not mean I could fill in any desired amount. The next check was $36,188. They weren’t actually trying to give me $36,188. No, the explanation was far more prosaic. The University was in the throes of replacing its accounting system and things weren’t working well at all. I was broke and couldn’t make the registration fee. Lowe took me to his bank and co-signed a loan of $275.00 for me so I could register.

He was nothing if not incredibly generous with his time and influence when he liked you. And for some reason that I’ve never been able to figure out, I guess he liked me. My more cynical readers will probably suspect other motives on Lowe’s part involving the fact that I was a Master’s candidate and not a Ph.D. or Postdoc, but I prefer to imagine that Lowe simply took a shine to me.

I dearly wish that I had been around when he passed and I miss Charles H. Lowe, Jr., very much.

Charles H. Lowe Jr. (Lynn Bielsky)